- Home

- Commentary

- Navigating disinformation, uncertainty, individualism and the poison apple of conspiracy

- If nothing changes nothing will change: the Voice referendum

- What can we learn from disaster communities?

- New year, a time to embrace the uncertainty of it all

- We could be non-binary

- Adaptive resilience vs safety paternalism

- Left wing, right wing? What just happened to politics?

- Covid, class and the addiction to certainty

- Neoliberalism, the Life World and the Psychopathic Corporation

- Democracy is about our bodies, not just our minds

- What’s your motivation: is it yourself or the change you’re making?

- Mind over matter: The world of abstraction is driving us to destruction

- The real threats to our liberty and survival

- Avoiding the abyss of conspiracy theories

- The difference between a legal system and a fantasy novel

- What’s a conspiracy and what’s just common garden variety corruption?

- Unpredictability, humility and an emerging anthropandemic

- The trilemma – climate change, economic collapse, and rising fascism

- Happy New Normal for the decade ahead

- Fires, liars and climate deniers

- The race to the bottom in australian politics

- Talking about lock-on devices – an article in ‘The Conversation’

- The Ponzi scheme is teetering

- Regenerative culture a key part of the blockade experience

- Staying sane in the late Anthropocene

- Extinction Rebellion

- Major parties have failed on climate, it’s time to rebel.

- Elections In The Late Anthropocene

- It is the Greens that are defeating the Nats and it’s all about your preferences

- Australia’s powerhouse of democracy and innovation is in the Northern Rivers

- Is identity politics a problem for the left?

- The climate emergency and the awful state of Australian politics

- Democracy and rights under threat in corporate police state

- Liberty, freedom and civil rights? Do any of us understand these things anymore.

- The forest wars are back, time to mobilise

- …more commentary

- Workshops

- News & Events

- Media

- A Flood of Emotions – Sydney Ideas Event

- Participatory democracy in the COVID era – SCU podcast

- Activism educator Aidan Ricketts explains how and why protests can be peaceful

- Bob Brown Is Taking “Shocking” Anti-Protest Laws To The High Court

- Anti protest laws could arrest nannas, seize tractors

- “They blinked first”

- Colin Barnett quick to protest against ‘activism degrees’ – The Australian, 16/10/2014

- ‘Degrees in activism’ put brake on growth – The Australian, 15/10/2014

- Magistrate throws out vexatious police case against CSG protesters

- Outrage over school PR ‘by stealth’- The Northern Star

- CSG clash a certainty

- Communities use new tactics

- Gas group attacks lecturer

- …more media

- Activist Resources

- Reviews

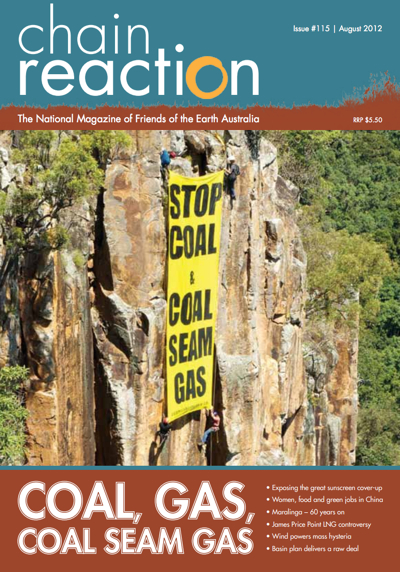

Chain Reaction Magazine: The power of locking your gate

Reprinted from Chain Reaction #115, August 2012,

Reprinted from Chain Reaction #115, August 2012,

The unconventional gas industry is on the march in Australia. Having moved to full production first in southern Queensland, there are now exploration permits issued or in the application process across vast tracts of NSW and Victoria and in other states and territories.

Unconventional gas refers to the infamous coal seam gas as well as tight sands gas, gas found in shale deposits and a variety of other problematic extraction processes. As the large-scale pollution of rural Australia by unconventional gas activities becomes better known, we are also witnessing the emergence of a rapidly growing and surprisingly mainstream social movement in opposition.

The social movement is a spontaneous response to a failure by our parliaments, politicians and legal systems to provide adequate protection for land owners, the water table and other environmental values from the rapacious, untested and dangerous activities of gas companies.

The Lock the Gate Alliance, which began in Queensland, is now a nationally incorporated body providing some national co-ordination of the hundreds of local groups that have sprung up to fight this threat. But predominantly the response to the gas industry is being propelled by a rapidly expanding grassroots movement with surprising vigour and a preparedness to utilise quite radical means of peaceful resistance to stop this industry.

Gasfield free community strategy

The first phase of community resistance took the form of the Lock the Gate strategy in which individual landowners refused to negotiate access arrangements with gas companies during the exploration phase. The strategy has proven very successful in rallying support in rural areas, but as a strategy used in isolation has some shortcomings which are now being addressed by a new strategic approach, the ‘gasfield free community strategy’. This strategy deliberately takes the focus of resistance away from the issue of private property rights and locates it firmly on the footing of community solidarity and introduces a landscape-wide approach to resisting unconventional gas activities.

The gasfield free community strategy was launched in the Northern Rivers of NSW, an area known historically for its use of peaceful direct action techniques to resist environmental destruction. The idea was to trial the idea first in the Northern Rivers so that it could be refined and adapted to other communities. The idea has taken off virally in NSW with over 16 communities enlisted and many more coming on board. The national Lock the Gate alliance has now endorsed the strategy for national roll-out and no doubt it will be an important part of the struggle in other states.

In a nutshell the gasfield free community strategy involves local communities holding public meetings and conducting face-to-face neighbourhood surveys to build support for a local resolution to become a gasfield free community. Once this is done ? and in NSW most participating communities record support in the 90 percentile ? communities erect signage on major roads, sometimes register with supportive local governments and mayors and then begin the substantial task of building internal networks to support peaceful direct action to prevent all gas activity in their own and surrounding communities. It’s like a cross between neighbourhood watch and the rural fire brigades.

One question that is constantly being asked is ‘What is the legal significance of putting up ‘Lock the Gate’ signs or declaring our communities ‘Gasfield Free’? The simple answer to this is that the Lock the Gate strategy is a very powerful form of resistance to mining companies and the gasfield free community strategy even more so, but at their heart they are political strategies, and are not expected to provide enforceable legal protection.

Ask a lawyer if locking the gate will make it impossible for mining companies to access your land and they will most likely give you a technical answer: mining companies have special rights granted under the relevant legislation to force a landowner to arbitration and ultimately to court to effectively force access. At first blush this is disturbing information and can cause many people to feel as though resistance is useless. But resistance is not useless, it is very powerful and here’s why.

Politics

The law does not exist in a vacuum; it is created by and maintained by the political process. Lawyers have a professional responsibility to give accurate advice to individual clients about their individual rights. Unfortunately taking a purely individual approach can run the risk of missing the social and political context of disputes like the current one over unconventional gas mining. It is a political dispute involving large numbers of people and when large numbers of people stand together in solidarity, the context within which the law operates changes significantly.

If a single landowner refused access on their own, a determined mining company could force access or simply step around them by gaining access to neighbouring properties. But when hundreds of landowners in a community, and particularly where all of the landowners refuse access, then the mining company is faced with a rapidly diminishing return if they try to force access into that community. The political and economic cost of launching numerous individual actions against landowners would inevitably cause a political backlash. Thus the real question is not what happens when one farmer locks the gate, but what happens when hundreds of farmers lock the gate?

But there are still some important limitations to the strategy of locking the gate. Because it’s a strategy based on private ownership rights, there is a danger that mining companies may be able to ‘divide and conquer’ by playing one landowner off against another.

This is where the gasfield free community strategy kicks in. The strategy takes resistance from the farm gate to the whole of community level; it aims to protect both private and public land and it resists all activities of miners, not just drilling and fracking. It means that the front line of resistance moves from your front gate to the frontiers of your community, and that you and your neighbours have agreed upon mutual assistance to help each other. It’s not that different to the way we all work together to fight other external threats like floods and bushfires.

So what happens where mining companies try to ignore these community declarations? Mining companies may aim to break the will of communities by going in regardless and requesting police assistance. We saw this last year in Kerry (south-east Queensland), but we also saw that the gas miners lost more than they gained. They gained a symbolic victory over a single blockade but at an unsustainable political cost. They may be able to break one blockade, they may be able to break several, but ultimately an industry and the politicians that support it cannot prevail against the solidarity of communities on a broad scale.

In a nutshell the problem for industry in breaking blockades is that even when they win on the ground they will lose in the court of public opinion. This is especially so if communities behave in a disciplined and peaceful way and respect the difficult role of police in these situations.

The need for blockades can be avoided if politicians listen to the voice of united communities and intervene to protect them from unconventional gas mining, but this not where we seem to be headed at present. The community is presently doing all it can to have its voice heard but if this does not wake up our politicians then communities may be forced to defend themselves. As the CSG Free Northern Rivers banner says: ‘Our resistance is non-violent but non-negotiable’.

The CSG free (Northern Rivers) website (csgfreenorthernrivers.org) is dedicated to providing freely available resources to help other communities to respond to the gas threat by going gasfield free. The site contains resources, ‘how to’ guides, forms and templates for joining this fast growing and powerful social movement. Further resources on how to plan community campaigns and practice peaceful direct action are available at aidanricketts.com, where you can also purchase copies of ‘The Activist’s Handbook’ online.

Aidan Ricketts is the author of the Activists Handbook, a prominent activism trainer, and a lecturer at the School of Law and Justice at Southern Cross University where his research and teaching specialisation is in the area of community activism and public interest advocacy.

Recent Posts

- Navigating disinformation, uncertainty, individualism and the poison apple of conspiracy

- If nothing changes nothing will change: the Voice referendum

- What can we learn from disaster communities?

- New year, a time to embrace the uncertainty of it all

- We could be non-binary about a lot more than gender

I like these sites

Community Organisations

- Code Green Tasmania

- CSG Free Northern Rivers

- Friends of the Earth Melbourne

- Generation Alpha

- Huon Valley Environment Centre

- Lock the Gate Alliance

- Nature Conservation Council NSW

- North Coast Environment Council

- North East Forest Alliance

- Plan to Win

- Rainforest Information Centre

- Save our Foreshore

- Still Wild Still Threatened

- The Change Agency

- The Wilderness Society